The first letter Joyce Means got from her state Medicaid agency said her coverage was ending on March 31 because her income was too high. The next letter, which the Arkansas Department of Human Services sent to her old address, said she would be terminated on May 1.

And the third letter, also mailed to the wrong address, said the Little Rock resident had until June 15.

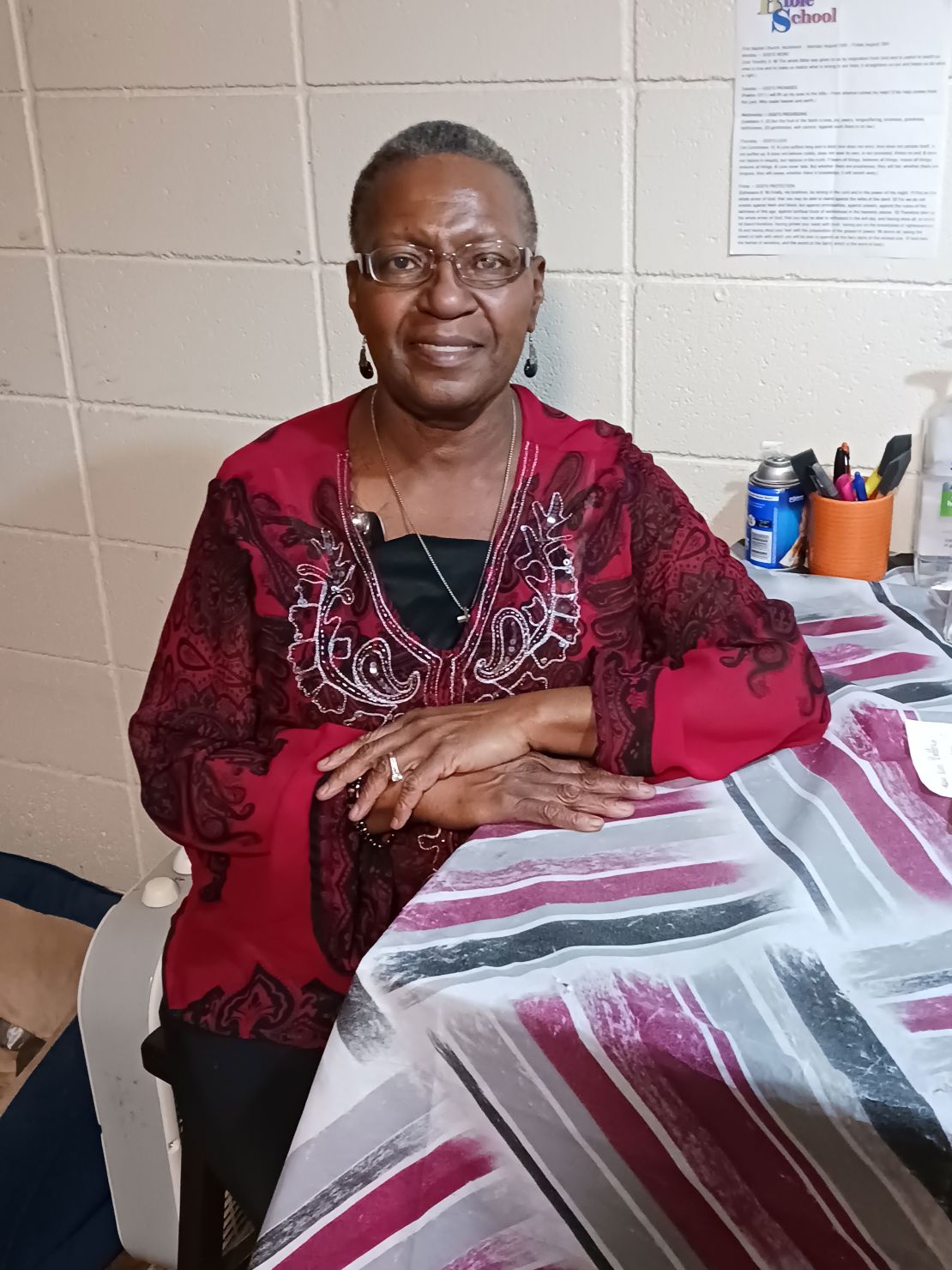

Though she visited the agency’s local office four times, Means could not get any answers. Finally, last week, she was referred to the agency’s Medicaid Resolution Center, which said her coverage was in the process of being restored – though she has yet to receive any paperwork proving that.

Means, 57, depends on Medicaid to pay the premiums and copays for her Medicare Advantage coverage, which she receives because she is disabled. The Medicare plan provides her with $180 a month in supplemental benefits that she needs to buy food.

After she received the first letter, Means called her Medicare insurer and switched to a less generous plan for April since she thought she no longer had Medicaid. That month she had to eat baloney, hot dogs and canned vegetables because she couldn’t afford fresh produce, meat and fish, which help her keep her diabetes in check. After receiving the subsequent letters, she went back to her old Medicare plan.

“It’s very stressful. I’m off. No, then I’m on. Then I’m getting cut off. Then I don’t know,” said Means, an activist with Arkansas Community Organizations.

Means, who takes 20 medications a day, isn’t the only one dealing with confusion and red tape. More than 93 million Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Plan enrollees are having their eligibility reviewed for the first time since the Covid-19 pandemic began.

Already, nearly 1.3 million people in 22 states have had their coverage terminated since April 1, when states were allowed to start dropping people for the first time since the pandemic began, according to KFF, formerly the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Of great concern to federal officials and advocates is that 76% of those losing coverage have been disenrolled for so-called procedural reasons, according to KFF, which is compiling state and federal data on the unwinding process.

This typically happens when enrollees do not complete the renewal application, often because it may have been sent to an old address, it was difficult to understand or it wasn’t returned by the deadline.

The disenrollment rate for procedural reasons varies widely by state. In Kansas, the share is 89%, followed closely by Connecticut and West Virginia at 87% each. At the other end of the spectrum, the rate is 28% in Iowa, which is extending deadlines and following up with residents, said Jennifer Tolbert, director of state health reform at KFF.

“High procedural disenrollment in states is a cause for concern,” Tolbert said. “We simply don’t know how many people were disenrolled but remain eligible.”

Most Medicaid enrollees are not aware that states can now resume terminating those deemed ineligible, a separate KFF survey found. Roughly two-thirds said their income and other circumstances hadn’t changed, suggesting they could continue to qualify for the health insurance program for low-income Americans.

Nearly half said they have never gone through the renewal process, KFF found, which could hinder them in holding onto their coverage now.

Restarting terminations

States had been barred by Congress from winnowing their Medicaid rolls since early 2020. In exchange, they received an enhanced federal match – which amounted to more than $117 billion in the first three years, according to KFF.

That prohibition ended on April 1, and states have 14 months to determine the continued eligibility of everyone in their Medicaid programs. Some states can do so automatically by reviewing available income and other data sources, while others require enrollees to submit applications and documentation.

The redetermination process is a huge lift for states. Adding to the challenge is that during the hiatus, Medicaid enrollment ballooned by more than 22 million people.

Overall, most people whose renewal reviews were completed retained their coverage. Some 38% were dropped, according to KFF.

The termination rate varies widely by state, however. Idaho, which is initially focusing on residents it no longer believes are eligible, has the highest rate at 73%, while Virginia’s share is 16%.

Estimates of the total number of people who will lose coverage vary – KFF has pegged it at 17 million, though many will find other sources of health insurance.

But that was based on a median disenrollment rate of 18%.

Tolbert expects the current rate of 38% to decline as more states report their data and move on to residents who likely still qualify. But if it remains high, many more people will have their coverage terminated than initially estimated, she said.

Warning from federal officials

The high rates of procedural disenrollments prompted Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra to send a second letter to governors last week reminding them of the importance of not terminating folks solely for administrative reasons.

“I am deeply concerned with the number of people unnecessarily losing coverage, especially those who appear to have lost coverage for avoidable reasons that State Medicaid offices have the power to prevent or mitigate,” he wrote.

Becerra reminded states that they could lose their remaining enhanced federal matching funds and have their terminations paused if they don’t comply with federal rules regarding the renewals.

Also, the agency announced several new flexibilities to make it easier for states to review enrollees’ eligibility. For instance, insurers who manage Medicaid coverage for a state can now assist their members in completing the renewal forms, and states can now delay procedural terminations for one month while they conduct targeted outreach.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is “aggressively” monitoring states’ redetermination efforts and working closely with them to address issues that arise, Daniel Tsai, the agency’s director of the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, told reporters last week.

The agency told CNN it has not issued any corrective action plans for non-compliance with federal requirements at this time.

Trying to help enrollees

Community groups across the nation are trying to guide Medicaid enrollees through the renewal process and assist them in regaining their coverage or finding alternate sources of insurance, such as on the Affordable Care Act exchanges.

In Houston, residents have to act fast to get an appointment at Epiphany Community Health Outreach Services, known as ECHOS. A day’s worth of slots usually fills up within an hour of becoming available, said Maricela Delcid, the nonprofit group’s benefits application assistance team leader.

A lot of clients don’t realize they need to send in updated information, Delcid said. She and one of ECHOS’ case managers, Angie Ochoa, say that many people they see are confused by the renewal packets and ignore them until they are told their coverage is being terminated.

Some Spanish-speaking families are receiving letters that are only in English. Other parents are afraid to reply because they are undocumented, even though their children are US citizens and eligible for Medicaid. And still other clients have moved and aren’t receiving the initial packets.

“It’s not knowing the whole unwinding process is going on right now,” Delcid said, noting that ECHOS is distributing flyers to families to inform them of what to expect.

Recently, Delcid helped a family who was having trouble renewing coverage for their two younger children. Though the mother had submitted proof of income and address, the state was now asking for a verification letter from an employer who offered the oldest daughter a job. However, the young woman never started working there because she went to college.

Delcid had to call the state Department of Health and Human Services’ 211 hotline and was told that the daughter needed to obtain a termination letter from the company since she is listed in the state system as having a job. The mother had to go to the employer’s main office to obtain it.

Sometimes Delcid and her clients are on hold for two hours before they reach a representative at the hotline. So she asks them to keep waiting outside or in their car while she helps other people. When someone picks up, they return to her office, requiring her to interrupt her session with another client.

It’s difficult for enrollees to work with hotline representatives on their own. There are often language barriers, and the newer staffers are not as well trained, Delcid said.

“Navigating 211 is not easy,” said Cathy Moore, executive director of ECHOS, whose largest source of funding for benefits application assistance is the Episcopal Health Foundation. “And they are not always able to help us with clients in all the ways we need them to.”

Multiple outreach measures

Efforts to contact enrollees and resolve any problems that arise vary by state.

Arkansas, which was among the first five states to start terminating residents’ coverage in April, has one of the fastest timelines to complete the redetermination process. The state legislature in 2021 required it be done within six months.

So far, nearly 150,000 people have been disenrolled, 82% of them for procedural reasons.

The state estimates that between 15% and 30% of the more than 420,000 Medicaid beneficiaries whose coverage was extended during the pandemic will no longer qualify.

If the Arkansas Department of Human Services cannot renew enrollees automatically through existing data sources, it sends them a renewal package by mail and then multiple notices before they are disenrolled, said Gavin Lesnick, the agency’s chief communications and community engagement officer. The department also attempts to reach them by text, email and phone when possible.

It is likely that many enrollees will not return their renewal packages because they are aware that they no longer qualify, Lesnick said.

“So a closure because of a procedural reason does not mean that the packet was not received or that the beneficiary was unaware of this process,” he continued. “In fact, extensive efforts have been made – and are continuing to be made – to ensure that Medicaid recipients know what to expect.”

Janette Hall, who lives in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, initially could not understand why she was told she’d lose her Medicaid coverage in mid-May because she made too much money. Then, she thought that her decision to start collecting Social Security when she turned 62 last year must have put her over the limit when added to her earnings as a cook for a nonprofit group.

Hall suffers from serious issues with her feet that make it hard for her to stand and work. She explored private health insurance but can’t afford the $78 monthly premium she was quoted. So she’s going to see whether she can get affordable coverage elsewhere, but meanwhile, she’ll focus on home remedies to keep her feet from getting infected.

“I’m going to be in that camp of people who aren’t going to be going to the doctor,” said Hall. “That’s what you do when you don’t want to get that bill coming to you.”